Here’s a brief article on the history of Sikh migration to Canada. The first Sikhs arrived in Canada in 1897 as part of the Hong Kong military contingent en route to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee

The first wave of Sikh migration to Canada was triggered in the early 1900s, with most of the migrant Sikhs moving to the country as laborers – logging in British Columbia and manufacturing in Ontario. Currently, Canada is home to the largest Sikh population outside India, with Sikhs accounting for 2.1% of the country’s population. The Sikh community in Canada has grown and thrived over the years. Today, Sikhs are an integral part of Canadian society and have significantly contributed to the country’s economy and culture.

Sikhs continued to have a turbulent history. As the Mogul Empire weakened, military and political conflict in Punjab escalated, to be subdued partially by the rise to power of the Sikh, Maharajah Ranjit Singh (1780–1839), who consolidated much of Punjab and Kashmir. Sikh converts increased dramatically during this period, as they did after Punjab was conquered by the British in 1846. Sikh men soon were an important part of the British Indian army, and thus migrated in small numbers throughout the British Empire. Canadian Sikhs are one of Canada’s largest non-Christian religious groups and form the country’s largest South Asian ethnic group. The vast majority of Sikhs live in Asia and approximately 2.6 per cent live in North America. Census figures suggest that there were 455,000 Sikhs in Canada in 2011, more than double the 1991 population estimate of 145,000. Immigration has been a key factor in the increase of Sikhs in Canada: Sikhs accounted for approximately five percent of the 1.8 million new immigrants who came to Canada during the 1990s, and today almost half of Canada’s Sikh population lives in British Columbia.

The first Sikhs came to Canada at the turn of the 20th century. Some visited Canada as part of the Hong Kong military contingent en route to Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee (1897) and the coronation of Edward VII (1902). The first immigrants arrived in 1904 and established themselves in British Columbia. More than 5,000 South Asians, more than 90 percent of them Sikhs, came to British Columbia before their immigration was banned in 1908. This population was soon reduced to about 2,000 through out-migration. Despite profound racial discrimination (Komagata Maru), Sikhs quickly established religious institutions in British Columbia. The Vancouver Khalsa Diwan Society was created in 1906 and through its leadership, Sikhs built their first permanent temple or gurdwara (“gateway to the guru”) two years later. By 1920, other gurdwaras had been established in New Westminster, Victoria, Nanaimo, Golden, Abbotsford, Fraser Mills, and Paldi. Each was controlled by an independent, elected executive board.

From the beginning, gurdwaras were the central community institutions of Canadian Sikhs. Through them, Sikhs provided extensive aid to community members in need. The dramatic fight to have the immigration ban rescinded was also organized through the temples. Temples were the focus of much anti-British revolutionary activity under the banner of the Ghadar Party, an organization that was founded in the United States in the early 20th century and quickly gained support in Canada as well.

Canadian Sikh religious institutions reached another stage of development in the 1920s when wives and children of legal Sikh residents were allowed entry to the country. Sikh religion provided the basis for a strong collective identity between the world wars, so very few Sikhs renounced the faith or married outside it. The main religious revision of the period 1920–60 was a tendency among second-generation men to become Sahajdharis — to cut their hair and beards to conform to Canadian dress codes. Some women wore dresses instead of the traditional Punjabi suit, the salwar kameez. Initiation into the Khalsa through Amritpahul became very rare.

In the 1960s and 1970s, tens of thousands of skilled Sikhs, some highly educated, settled across Canada, especially in the urban corridor from Toronto to Windsor. As their numbers grew, Sikhs established temporary gurdwaras in every major city east of Montréal. These were followed in many instances by permanent gurdwaras and Sikh centers. Most cities now have several gurdwaras, each reflecting slightly different religious views, social or political opinions, or caste backgrounds. Through them, Sikhs now have access to a full set of public observances. Central among these are Sunday services, and in most communities, the services are followed by langar (a free meal) provided by members of the sangat (congregation). Another important development within the Sikh diaspora, including Canada, is independent schools specifically designed to fit the needs of Sikh children. Khalsa schools are funded either exclusively through funds raised by Sikhs or through a combination of private and public funding available to faith-based schools within some provinces. While most Sikh children attend public schools, Khalsa schools offer Sikhs a religion-based education with a specific focus on Sikh history, culture, and Punjabi language training, while at the same time following each provincial ministry’s curriculum guidelines. Other important initiatives among Sikhs are the growing number of camps for children, youth, and women’s camps sponsored by Sikh sangats throughout Canada. These are often known as Gurmat camps, Gurmat referring to the “teachings of the Gurus.” While many of these camps are based within local gurdwaras, a number of camps invite attendees from across Canada

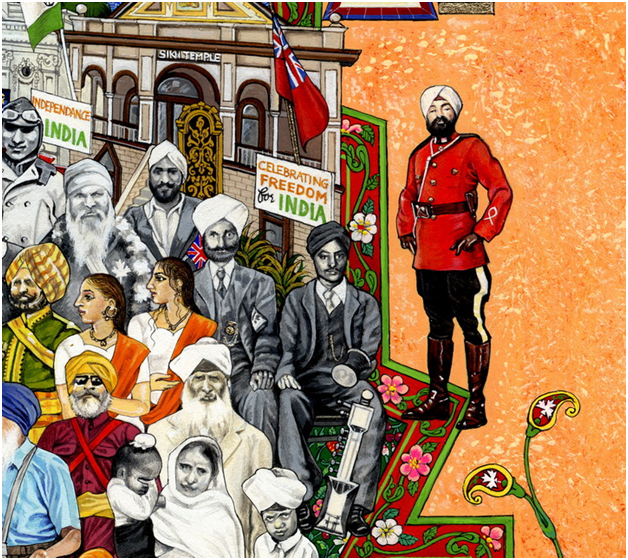

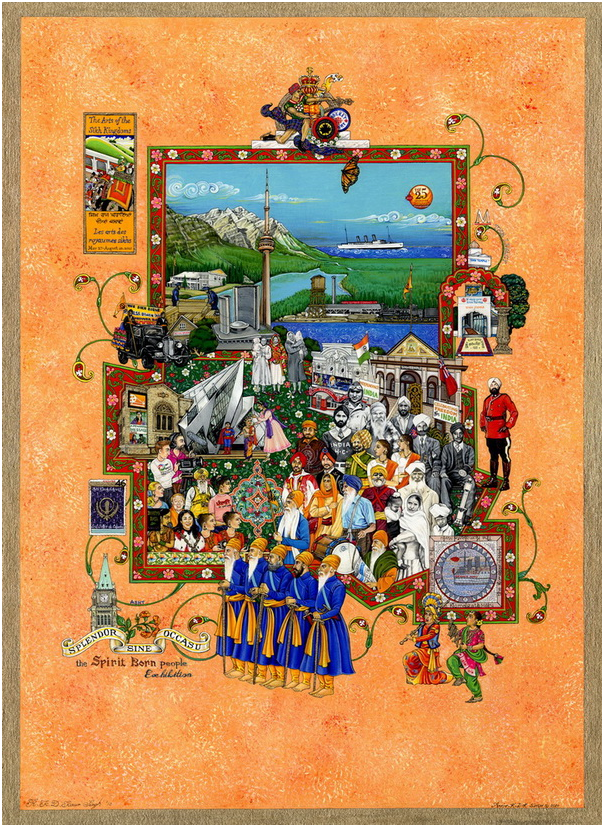

This painting was commissioned by the ROM in 2006, completed in 2010, and is now part of the ROM’s permanent collection. It was created by renowned contemporary artists, The Singh Twins, in their “past-modern” style (a play on the term “post-modern”), combining techniques of traditional Indian painting and modern content. The work is a tour-de-force reflecting the historical and cultural evolution of the Sikh Diaspora in Canada. It is currently on display in the Sir Christopher Ondaatje South Asian Gallery. Read from top to bottom, the painting moves from the scenic West coast of Canada to the urban metropolis of Toronto and from early migrants to contemporary Canadian society. It features Sikh contributions in the early twentieth century to the infrastructure of Canada (Canadian Pacific Railway and Liner, Mayo and Doman Lumber Companies), their struggles and triumphs to establish communities (the Komagata Maru Incident, establishing gurudwaras, and installation of the first Guru Granth Sahib in Vancouver), and their participation in key positions in government, business, media, and arts (Parliament building in Ottawa, the first turbaned officer of the RCMP, OMNI TV, and dhol player). Other decorative details provide a symbolic dimension: the Monarch Butterfly represents Sikh migration and the combined marigold and maple leaf motif within a paisley represents Canadian Sikh identity. Even the ROM is included to represent the key role played by Canadian cultural institutions in preserving and encouraging the heritage of diverse communities that are now part of the Canadian fabric

Sikh Diaspora in Canada

- Significant Population: According to the 2021 Canadian census, Sikhs account for 2.1% of Canada’s population, making Canada home to the largest Sikh population outside India.

- Historical Migration: Sikhs have been migrating to Canada for over a century, primarily driven by their involvement in the British Empire’s armed services.

- Expansion of the Empire: Wherever the British Empire expanded, Sikhs migrated, including countries in the Far East and East Africa.

Early Years of Sikh Migration

- Queen Victoria’s Jubilee: Sikh migration to Canada began in 1897 during Queen Victoria’s Diamond Jubilee. Kesur Singh, a Risaldar Major in the British India Army, is considered one of the first Sikh settlers to arrive in Canada that year.

- Laborers and Sojourners: The first significant wave of Sikh migration to Canada occurred in the early 1900s, with most migrants working as laborers in British Columbia’s logging industry and Ontario’s manufacturing sector.

- Intent to Remit: Many of the early Sikh immigrants were sojourners, intending to stay for only a few years and remit their savings back to India.

Challenges and Pushback

- Hostility and Prejudice: Sikh migrants faced hostility from locals who perceived them as job competitors. They also encountered racial and cultural prejudices.

- Tightened Regulations: Due to mounting public pressure, the Canadian government imposed stringent regulations, such as requiring Asian immigrants to possess a specified sum of money and arrive only via a continuous journey from their country of origin.

- Komagata Maru Incident: In 1914, the Komagata Maru incident occurred, where a ship carrying 376 South Asian passengers, mostly Sikhs, was detained in Vancouver for two months and then forced to return to Asia. This incident resulted in fatalities.

Turning Point after World War II

- Relaxing Immigration Policy: After World War II, Canada’s immigration policy shifted for several reasons, including a commitment to the United Nations’ stance against racial discrimination, economic expansion, and a need for laborers.

- Importance of Human Capital: Canada turned to third-world countries for the import of human capital, leading to a decline in European immigration.

- Points System: In 1967, Canada introduced the ‘points system,’ focusing on skills as the main criterion for non-dependent relatives’ admission, eliminating racial preferences.

Conclusion

The history of Sikh migration to Canada spans over a century marked by challenges, prejudice, and policy changes.

Today, Canada is home to a thriving Sikh community, showcasing the transformative journey from early struggles to a more inclusive and skill-based immigration system.

Assessing the Relationship of Sikh-Canadians with Canada and India

From their initial migration to Canada, Sikhs were met with profound racial discrimination. This discrimination took the international stage in April of 1914 when the Komagata Maru, a Japanese steamship ship carrying Sikh passengers, was refused entry into Canada. Nonetheless, Sikhs established strong religious institutions through gurudwaras or Sikh temples. South Asian immigration was completely halted until 1920 when wives and children of Sikh-Canadians were finally allowed to enter the country.

In contrast to the American society depicted as a ‘melting pot,’ Canada is seen as a ‘mixed salad’ of cultural differences today, where all faiths, ethnicities, and traditions are accommodated instead of assimilated. However, throughout the twentieth century, white Canadians were resistant to non-white immigrants. From the 1920s to the 1960s, Sikhs in Canada experienced a religious revision. Instead of maintaining traditional practices, children of immigrants adopted Sahajdhari practices. Being a Sahajdhari meant that men were able to break from practices that prevented them from cutting their hair and adopting Canadian dress codes.

The second wave of immigration coincided with the birth of the Sikh separatist movement in India. Even though Sikhs and Hindus lived peacefully amongst each other for centuries, tensions arose in the late 1960s when the Sikh population in Punjab gained economic prosperity following the Green Revolution in India. With growing wealth and a flourishing agricultural industry, Punjabi society slowly became increasingly more detached from mainstream Indian culture. In an effort to relieve political stress, Indian Prime Minister Indra Gandhi attempted to transfer the city of Chandigarh to the Punjab province. However, with no success, this olive branch was never fully executed, further strengthening distrust of the Prime Minister amongst the Sikh population. By the 1980s, the Sikh Khalistan movement was in full force.

The Khalistan movement is a separatist movement that calls for an autonomous Sikh nation-state. As scholar Stephen Van Evera suggests that nationalist movements are inherently violent, the Khalistan movement quickly turned violent against the Indian state. In 1984, the Indian army staged a siege of the Golden Temple, a sacred Sikh shrine, in an effort to take down Sikh extremists. After the altercation, more than 1,000 people died, and the temple was nearly destroyed. The results of the siege ignited support from the Sikh diaspora in Canada, both financially and socially. Sikhs in Canada began to fund the separatist movement in India, which resulted in the deterioration of the relationship between Canadian Sikhs and their Indian homeland. Additionally, the sudden violence of the Khalistan movement caused a mass migration of Sikhs to Western countries, most prominently in Canada.

The growing Sikh population in Canada has recently become a concern to India. Within the last year, Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi has become wary of Canada and their foreign policies. Indian officials worry that Western governments have become sympathetic to the Sikh separatists and will act in their interests when considering foreign policy. In 2017, the Canadian Parliament declared the siege on the Golden Temple in Punjab a genocide committed by the Indian state against the Sikh religious minority. This genocide declaration has further strained the relationship between Sikh Canadians and the Indian State. Being a stateless nation, the Sikh population in Canada has essentially become a political organization where they have gained the agency to influence politics in Canada. Thus, the Canadian government has been an active participant in accommodating Sikh-Canadians and Sikh immigrants. On March 2, 2006, the Canadian Supreme Court notably struck down a ban on allowing Sikh students to carry a kirpan, a ceremonial dagger, in school.

Pop culture is another important indicator of the relationship between white Canadians and Sikhs. Within the past century, major pop culture figures of Sikh roots have gained popularity among all Canadians. Most famously, Lilly Singh, also known as iiSuperwomanii, was the highest-paid female on the video hosting website YouTube in 2016. She is a vocal Sikh who was born and brought up in the Ontario province of Canada.

Sikh immigrants were not initially welcomed with open arms into Canada. Due to racial discrimination by white Canadians, South Asians had a slow assimilation into Canadian society. However, political tensions with the Indian state weakened the connection Sikh immigrants had with their homeland. Hence, integration and assimilation into a new national identity were possible. Sikhs in Canada have risen to political power with nearly twenty Sikh Members of Parliament. While Sikh-Canadians’ connection to India may have been weakened, Sikh identity in Canada was strengthened due to support for the Khalistan movement and Sikh nation, instead of the actual Indian state.